I'd told myself I was going to take a break from writing about food, but that decision seems to be in conflict with my determination to write about linguisticky things that come up in my day-to-day doings...and it seems like all I do is eat.

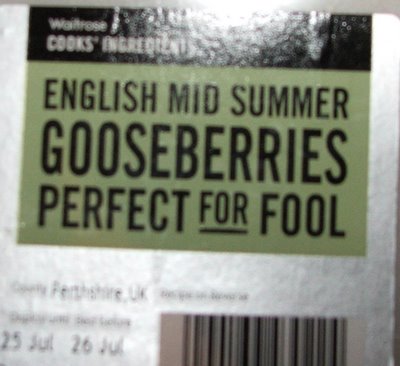

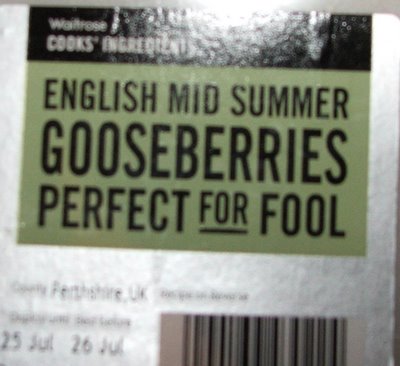

Better Half is mad for (AmE=crazy about) gooseberries, a fruit I'd never experienced in the US, though I did know that the kiwi (fruit; BrE) used to be called the Chinese gooseberry. Anyhow, this is the label on the punnet (BrE*) that he bought this week.

I said to him, "Sweetie, you don't have to buy things just because it says on the label that they're perfect for you."

Better Half was not amused. It is a trial to live with me, I must admit.

Gooseberry fool is a traditional British treat, which involves gooseberries (duh), sugar and lots and lots of cream. BH made some when his nan (=grandma) visited Friday, but in an attempt to make it less calorific, replaced some of the cream with yog(h)urt. (Myself, I think that yog(h)urt has its place, but that any excuse to eat cream should not be taken lightly.) Fools can be made with other fruits as well, but gooseberry fool is the king of fools.

Now, I have to give two links for recipes, suitable to each continent's measures and ingredients. For the American version, click here, for a British version, click here. Some recipes include custard in the fool, but that's newfangled tomfoolery.

If it's just about berries, sugar and cream, why do you need different recipes? Well, because cream just isn't the same in the two places. In the US, there are three (basic) types of cream: light cream, heavy cream and whipping cream, which I always thought was a con, because it doesn't seem to be terribly different from heavy cream. In the UK, on the other hand, there are single cream, double cream, whipping cream and clotted cream. Clotted cream has been subjected to heat and is very butter-like, and perfect for spreading on scones with a bit of strawberry jam. As for the first two, one might believe that these are easily translated. Single cream = light cream and double cream = heavy cream. Right?

Wrong!

...as I discovered when I first made my chocolate mousse recipe here. It called for heavy cream, so I bought some double cream. Some double cream is label(l)ed "suitable for spooning"--when you scoop a dollop onto your cake, it'll keep its shape. I made my mousse with non-spooning double cream, but it was still much heavier (48% butterfat) than a heavy cream (36-40%). The mousse was perfectly edible, but it was more like eating a truffle than a mousse. No one could finish their portion, except for BH's sister's better half, The Gardener. The man has the sweetest tooth (full of cavities) and the kind of metabolism that I mention in my prayers. Not only did he finish his own, he finished everyone else's plus the "safety serving" I'd held back in the fridge.

Single cream and light cream have around 18% butterfat. Whipping cream has 30-40%. So, if you have a US recipe that calls for heavy cream, use whipping cream if you're in the UK. North America also has half-and-half, which has 10-12% fat. I've seen it claimed that single cream and half-and-half are the same thing, but really you have to add a little milk to single cream to make it like half-and-half.

Cream is a more serious business in the UK because it is so central a part of pudding (AmE = dessert). Cream is poured over most puddings/desserts, including a cake, true puddings ("sweet dessert, usually containing flour or a cereal product, that has been boiled, steamed, or baked." --American Heritage Dictionary), apple crumble (AmE = apple crisp), or even fresh fruit salad (which, even though I am a great fan of cream, I find a little disgusting). For some desserts/puddings, one is offered warm, pourable custard as an alternative to cream. The only puddings/desserts that I can think of that one doesn't always get cream, custard or ice cream with are those that are already made of cream, custard or ice cream, like fools or trifle--a concoction of sponge cake, (BrE) jelly (AmE=gelatin, usually called by the brand name Jell-o), custard, sherry, cream, and jam. In the US, one might get whipped cream or ice cream with cake, pie or crumble/crisp, but not poured cream.

Another oddity in the gooseberry label: it says "ENGLISH MID SUMMER GOOSEBERRIES", but the county of origin (almost legible in the photo) is Perthshire--in Scotland. I fear for Waitrose (supermarket) if the Scottish nationalists pick up on this slight. (I could say something about the space in mid summer, but hyphenation will have to wait for another post.)

* A note on punnet. Historically, this word refers to a shallow basket for collecting fruit, but these days it's the (often plastic) container that soft fruits are sold in. In AmE, we tend to say a pint of strawberries, referring to the amount, rather than the container, whereas hereabouts one buys a punnet of strawberries. When I refer to the container itself, I'd probably say a pint box. If it were a bushel of strawberries, I'd probably call the container a crate, especially if it were wooden.

Better Half is mad for (AmE=crazy about) gooseberries, a fruit I'd never experienced in the US, though I did know that the kiwi (fruit; BrE) used to be called the Chinese gooseberry. Anyhow, this is the label on the punnet (BrE*) that he bought this week.

I said to him, "Sweetie, you don't have to buy things just because it says on the label that they're perfect for you."

Better Half was not amused. It is a trial to live with me, I must admit.

Gooseberry fool is a traditional British treat, which involves gooseberries (duh), sugar and lots and lots of cream. BH made some when his nan (=grandma) visited Friday, but in an attempt to make it less calorific, replaced some of the cream with yog(h)urt. (Myself, I think that yog(h)urt has its place, but that any excuse to eat cream should not be taken lightly.) Fools can be made with other fruits as well, but gooseberry fool is the king of fools.

Now, I have to give two links for recipes, suitable to each continent's measures and ingredients. For the American version, click here, for a British version, click here. Some recipes include custard in the fool, but that's newfangled tomfoolery.

If it's just about berries, sugar and cream, why do you need different recipes? Well, because cream just isn't the same in the two places. In the US, there are three (basic) types of cream: light cream, heavy cream and whipping cream, which I always thought was a con, because it doesn't seem to be terribly different from heavy cream. In the UK, on the other hand, there are single cream, double cream, whipping cream and clotted cream. Clotted cream has been subjected to heat and is very butter-like, and perfect for spreading on scones with a bit of strawberry jam. As for the first two, one might believe that these are easily translated. Single cream = light cream and double cream = heavy cream. Right?

Wrong!

...as I discovered when I first made my chocolate mousse recipe here. It called for heavy cream, so I bought some double cream. Some double cream is label(l)ed "suitable for spooning"--when you scoop a dollop onto your cake, it'll keep its shape. I made my mousse with non-spooning double cream, but it was still much heavier (48% butterfat) than a heavy cream (36-40%). The mousse was perfectly edible, but it was more like eating a truffle than a mousse. No one could finish their portion, except for BH's sister's better half, The Gardener. The man has the sweetest tooth (full of cavities) and the kind of metabolism that I mention in my prayers. Not only did he finish his own, he finished everyone else's plus the "safety serving" I'd held back in the fridge.

Single cream and light cream have around 18% butterfat. Whipping cream has 30-40%. So, if you have a US recipe that calls for heavy cream, use whipping cream if you're in the UK. North America also has half-and-half, which has 10-12% fat. I've seen it claimed that single cream and half-and-half are the same thing, but really you have to add a little milk to single cream to make it like half-and-half.

Cream is a more serious business in the UK because it is so central a part of pudding (AmE = dessert). Cream is poured over most puddings/desserts, including a cake, true puddings ("sweet dessert, usually containing flour or a cereal product, that has been boiled, steamed, or baked." --American Heritage Dictionary), apple crumble (AmE = apple crisp), or even fresh fruit salad (which, even though I am a great fan of cream, I find a little disgusting). For some desserts/puddings, one is offered warm, pourable custard as an alternative to cream. The only puddings/desserts that I can think of that one doesn't always get cream, custard or ice cream with are those that are already made of cream, custard or ice cream, like fools or trifle--a concoction of sponge cake, (BrE) jelly (AmE=gelatin, usually called by the brand name Jell-o), custard, sherry, cream, and jam. In the US, one might get whipped cream or ice cream with cake, pie or crumble/crisp, but not poured cream.

Another oddity in the gooseberry label: it says "ENGLISH MID SUMMER GOOSEBERRIES", but the county of origin (almost legible in the photo) is Perthshire--in Scotland. I fear for Waitrose (supermarket) if the Scottish nationalists pick up on this slight. (I could say something about the space in mid summer, but hyphenation will have to wait for another post.)

* A note on punnet. Historically, this word refers to a shallow basket for collecting fruit, but these days it's the (often plastic) container that soft fruits are sold in. In AmE, we tend to say a pint of strawberries, referring to the amount, rather than the container, whereas hereabouts one buys a punnet of strawberries. When I refer to the container itself, I'd probably say a pint box. If it were a bushel of strawberries, I'd probably call the container a crate, especially if it were wooden.