Thomas West was responsible for last week's post topic, and here he is again, having tweeted:

Reading that, I first thought "I think that's a mark of my Britification—the singular is probably what I'd say now." I then wasted some time searching things I'd written (on Twitter, on this blog, on my hard drive) that used the expression, and found none. What else are lockdown Sunday mornings for?

But then I thought more and thought "But do

at a loose end and

at loose ends always mean the same to me?"

Loose ends, of course, need to be metaphorically tied. Both Englishes talk about, say, a project having loose ends, which need to be tied off or tied together to give us something finished—that won't unravel. Here I'm just interested in the

at expression, which has more particular uses, and in which the metaphor gets a little more buried. No one says

I'm at loose ends, so I'm going to tie them or

I'm at a loose end, so I'm going to tie it/myself up. Maybe when you're at

a loose end, you can get the image of hanging idly, or when you're at loose ends you have a sense that you have "ends" that you don't know what to do with.

The

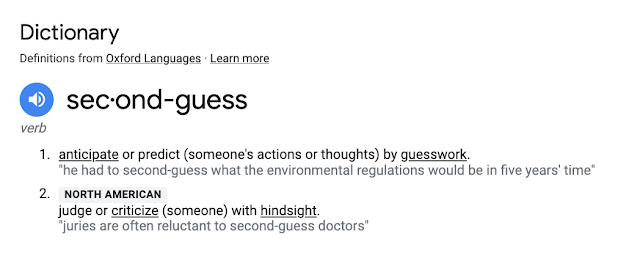

Collins Dictionary website can be useful for looking into such things as it has a whole bunch of dictionaries together: the Collins COBUILD (meant for English learners, BrE-based but more apt to cover American variants), Collins English Dictionary (which is BrE-based), and Webster's New World Dictionary (WNW; AmE-based).

COBUILD presents at a loose end as a feeling of boredom, and simply states that

at loose ends is the American equivalent. (

Collins English Dictionary defines it as "without purpose or occupation".)

Where Collins has one definition for the singular (and by extension, the plural) phrase, WNW gives three senses for the plural phrase:

Now, all of those senses are very similar, and so this looks like a difference in lexicographical style—whether you lump similar uses together or split them into definitions that describe more specific situations where the phrase is used. The Collins "without purpose or occupation" could be mapped onto senses 2 ('without anything definite to do') and 3 ('unemployed') in WNW. It's the 'unsettled, disorganized' bit that feels a bit different from COBUILD's 'bored'. What's unclear from that definition is whether it's people or situations that are unsettled and disorganized—that is, "I am at loose ends" versus "We left the project at loose ends".

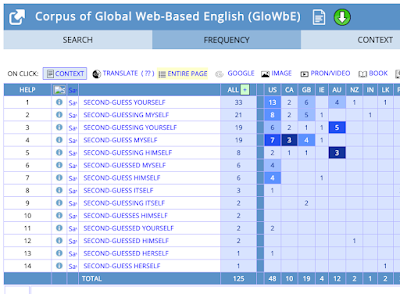

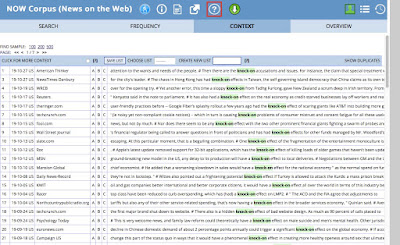

So, I had a little look in the

GloWBE corpus, to see if I could find differences in how the singular phrase is used in BrE (42 unique usable examples) versus the plural phrase in AmE (20). There are few enough of these that I can look at all the examples. (The four "AmE" examples for the singular phrase were actually from British sources, so I won't consider them.)

All of the examples in both countries are talking

about people, rather than situations. Some seem to be in the 'disorganized, confused' sense—and I had to wonder in some of these cases if the writer was thinking of the phrase

at [someone's] wit's end. These 'confused" examples were there in small numbers in both countries, so it is looking like the expressions really are equivalent in AmE and BrE, it's just a matter of different dictionaries splitting the senses more or less.

- BrE source: any advice will help as im at a loose end surely there is something i can do to sort this out???

- AmE source: As a former (public school) teacher I was at loose ends how to educate my daughter (in context, this meant: didn't know which choice to make)

Otherwise, most of the examples in both places signify 'having nothing particular to do' or 'idle'.

Merriam-Webster, another US dictionary, gives only one

definition, which seems to combine all three of WNW's senses, and makes

it clearer that this expression is used of people, rather than of their

situations:

US

not knowing what to do : not having anything in particular to do

But I found two things in the data interesting:

1. As someone with both phrases in my repertoire, I felt like I'd have to use the plural with a plural subject. That is, I [singular] may be

at a loose end, but my friends [plural] would be

at loose ends, because they each have their own loose end. The data had five British plural

at loose ends and 3 of those had plural subjects, but the BrE singular

at a loose end was also used with plural subjects. This might be like

collective noun agreement, in that the BrE speaker might be considering the semantic number more than the grammatical number: we are at

loose ends if we're separately loose, but we are at

a loose end, if we're reacting to a singular situation. That said, I don't think the data really show this in most cases. In the first example below, we get a BrE plural verb with a grammatically singular (BrE)

football club name, but their

loose end is singular. (Note that the collective plural in BrE isn't as semantically driven as some people—even me in the linked-to blog post—claim. I discuss that in chapter 6 of

The Prodigal Tongue.)

- BrE singular end, plural subject:

- AC Mill Hill were at a loose end and started to play the hopeful long balls.

- BrE plural ends, plural subject:

- tens of thousands of men with military training are put at loose ends each year

2. AmE has a few examples of

at loose ends with [one]self, which seems to have a particular sense of feeling 'lost' and 'purposeless'. BrE doesn't seem to have

at a loose end with:

- AmE: Years ago I had a client who always seemed to be at loose ends with himself.

None of this has addressed Thomas's question "why?" "What's the difference?" questions are answerable. "Why do they differ" questions are often not, both because the evidence is not available and because change in idioms is rarely a simple straight line. Things that change don't simply change once, they change thousands of times in small and diverse ways before they arrive somewhere else.

The thing to keep in mind here is that

things had loose ends centuries before

people did. People were talking about

loose ends in other kinds of contexts, so if the expression as applied to people started in the singular (and it probably did), then it would be unsurprising if the plural (about things) noun phrase (

loose ends) affected the singular (about people) prepositional phrase

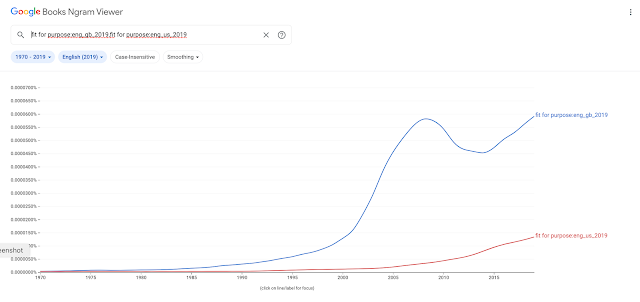

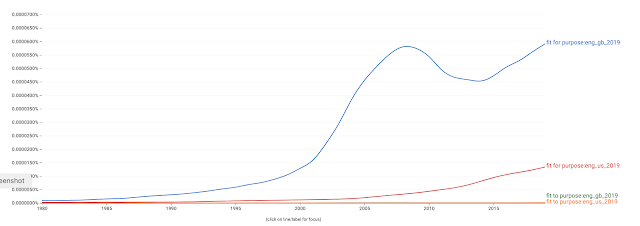

(at a loose end). When I searched for the

at phrases in Google Books, there were lots of

loose ends in the early 1800s, but the OED only notices the 'idle person' meaning from the 1850s onward. So, I put an

am in front of the

at in my searches (in order to make sure that the loose ends belonged to people) and got this (there are no British hits for

am at loose ends). That seems to confirm that the plural expression came later, with the singular having some presence in AmE, then falling out in the first half of the 20th century:

But the other thing to note about origins is that the phrase was not originally

at a loose end in BrE either. The

at took a long time to settle down. Early examples in the OED have

after a loose end and

on a loose end, and the OED also notes another expression from more than 100 years earlier than

at a loose end:

at the loose hand.

- 1742 R. North & M. North 77

He was weary of being at the loose hand as to company.

So perhaps the metaphor was originally one of idle hands rather than fraying rope? Is that why we don't talk about tying up our loose ends, because the expression didn't evolve from a nautical rope metaphor? At any rate, as idioms evolve, they often influence each other and that could have happened here

.